Charter schools operating in conflict with local school districts is an issue that’s been around for as long as we have had charter law. As such, we are reliant on state legislation to make collaboration happen more. The U.S. Department of Education’s Charter Schools Program (CSP) has a few key roles in supporting this, they:

Charter schools operating in conflict with local school districts is an issue that’s been around for as long as we have had charter law. As such, we are reliant on state legislation to make collaboration happen more. The U.S. Department of Education’s Charter Schools Program (CSP) has a few key roles in supporting this, they:

- Strengthen authorization

- Provide access to facilities and funding

- Provide enrollment and services for disadvantaged students

- Support expansion and replication (including ties to low-performing schools).

The Center on Reinventing Public Education’s (CRPE) ongoing research helps track collaboration efforts between charters and district schools across the nation. They recently released a report, “How States Can Promote Local Innovation, Options, and Problem-Solving in Public Education” which covers this topic. Some of the key report findings include:

- Collaboration is often treated as a “side project” or “forced marriage”

- Local politics impact incentives and the likelihood of success

- Cities that do sustain progress are working within local constraints and making smart choices on what to collaborate around

The National Charter School Resource Center recently presented a webinar covering these issues and what organizations like the CSP and CRPE are doing to help. This session included two panelists working with CRPE, Senior Research Analyst Sarah Yatsko and Jordan Posamentier, Deputy Director of Policy. They share their research gleaned from studying the role of collaboration between local district schools and charter schools.

Facilitator Alex Medler, Senior Director of the National Charter Schools Resource Center, led the discussion around three key issues local districts face – state mindset, leveraging funding grants and resolving local district-charter conflicts to clear the path for collaboration.

The overarching focus of the discussion was on the state’s role in collaboration between local districts. When applying for a federal grant, every state is required to explain in their application how they plan to support collaboration, but deciding how to apply funding toward local district-charter collaboration doesn’t usually end up being a high priority.

“Given the competitive nature of school choice, limited education funding and rampant misconceptions on both sides, this is not surprising,” said Medler.

Although the history between charters and traditional district schools has been contentious, things are starting to change. Traditional district schools and charters are increasingly seeing the value in coming together. But the role of the state in fostering cross-sector collaboration is essential.

“The way the state thinks about district-charter relations, problem-solving and collaboration has a trickledown effect to the local level. Without state involvement, kids lose opportunities due to sector divide, sectors resist coming together on their own and need strong leadership to insist on forging ahead despite politically challenging environments. State leaders can influence local tone by adopting mindsets conducive to collaboration. This in turn helps students and their families navigate what are becoming more and more complex choice environments,” explains Posamentier.

In summing up the CRPE’s stance on district-charter collaboration, Yatsko says that we see collaboration as “a necessity, not a nicety.”

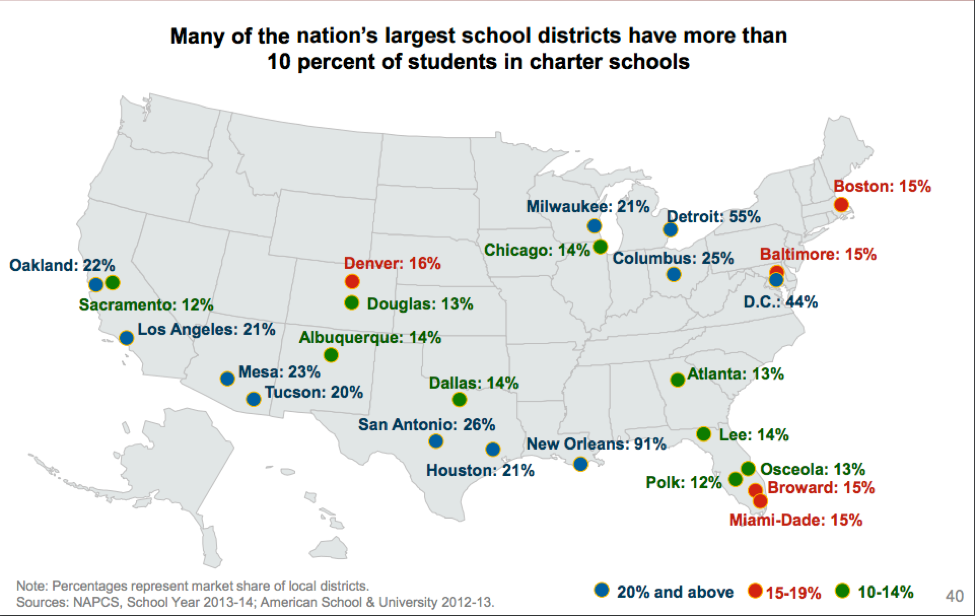

“Now we see with the growth of the charter sector, in many cities, the charter sector is no longer just a side project that can chug along on its own. It’s become a major part – in some cities over 50 percent of the public educational landscape – and is no longer something these sectors can efficiently operate without considering the impact one has on the other. So, we see it as a necessity,” highlighted Yatsko.

When the state mindset is on collaboration, legislative frameworks and SEA structures get passed down to the local level. In many states (like Georgia, Rhode Island, Massachusetts), they are framing their educational philosophy around personalized learning and really looking at whether or not schools are responding to family need.

According to the report data, looking into state level grants strategically can create positive incentives and capacity for local school leaders. Prioritizing start-up and two-way dissemination grants for both district and charter schools that commit to collaboration is one approach. They can create funding set-asides for cross-sector turnaround partnerships. Arizona and Massachusetts are good examples of states that took opposite approaches to how mindset can affect the local level. In Arizona, it’s a competition-based philosophy where the two sectors are meant to be independent and competing with each other. However, there’s still no collaboration at the local level in Arizona. In Massachusetts, there’s a strong partnership between traditional public schools and charters – in fact, charters were envisioned as the research and development department for the traditional sector and they built dissemination into the charter statute.

States can also encourage collaboration by resolving some tougher local conflicts. These conflicts revolve around two things:

- Access issues (enrollment, transportation, buildings, safety services)

- Funding issues (what level of fees should occur between the school and the authorizer)

One outcome is for the state to stipulate this, and direct charter funding from the state versus through the district.

States should consider their own sector neutrality and a “focus on what works” mindset rather than a “who works” mindset. They can also prioritize bilateral learning and strong partnerships in grants and turnaround efforts. It also works to resolve intractable local battles at the state level through legislation. One idea suggested for accomplishing this is to allow for shared test scores when there is school turnaround so that the whole city can claim the wins that the charter can provide. Other ideas toward ensuring that all students move toward improvement: encourage localities to adopt shared performance metrics, get schools to adopt shared enrollment systems, and promote objective standards for local authorizing.

The key takeaway here is that sectors working together locally can help states accomplish big goals toward school improvement and equity. Local collaboration efforts have only taken us so far, but the state can help drive them toward improvement. Effective state involvement in local collaboration requires intention, dedication and political savvy. Yatsko believes that states need to focus on small ways to make collaboration “sticky,” meaning, outlast the leaders involved and become sustainable.

“Interesting examples are in places like Sacramento, CA that didn’t go too far in terms of collaboration, but there was an agreement across districts and charter sectors around the leasing of charter schools and district facilities – it was a one year and changed to a five year lease.”

The CRPE will continue to research and track efforts to increase collaboration between traditional district and charter schools. CRPE team encourages contributions from those who feel their state’s viewpoint is not included in the current research. Reach out to them on their website.